“Paradise Not Found”

Hyman Klinkle

Without diminishing the legacy of the buccaneer Henry Medillo, it is a historical fact that Poco Cabesa’s real claim to fame rests on the shoulders of Hyman Shlomo Klinkle. Perhaps that should be restated, because the treasure that lured Hyman Klinkle to Poco Cabesa after the American Civil War was guano; i.e., dried bird-droppings. Enormous quantities of it. To most, this island attribute led to revulsion and a rapid retreat. To Hyman Klinkle it was the sweet smell of opportunity.

Early in the 19th century, farmers discovered the efficacy of manufactured fertilizer. Making fertilizer required phosphates. And phosphates required… well, you get the idea.

[Note: It has been argued that today’s international fertilizer industry has its roots in the guano taken from hundreds of islands like Poco Cabesa: Ref. unpublished doctoral theses by Mbeki Eugene Allan, “Guano Harvesting in the Late 19th Century Mediterranean;” and Phil Fleischer, “Gone with the Guano — The Economic Impact of Bird Droppings on Modern Capitalism”]

Klinkle Rock

Unfortunately, fertilizer made using low-grade American bat guano didn’t quite cut the mustard, so to speak. And it was also essential to the production of gunpowder and other explosives. Suddenly, at mid-century, the United States faced the frightening prospect of a guano gap.

This dire threat to the Republic gave Congress something to do before the Civil War besides argue about states’ rights and bludgeon one another with walking sticks. What they did allowed Hyman Klinkle to claim-stake the entire island in 1878 under the U.S. Guano Act of 1856.

In its infinite wisdom, this Act of the 34th Session of the United States Congress legislated that any unclaimed and uninhabited island anywhere in the world that possessed guano was automatically deemed a U.S. territory if an American citizen claimed it first. The Act’s stated purpose was to protect U.S. access to this precious resource, although some insisted it was a sell-out by political cronies associated with the Chicago Mercantile Board. Others claim it was just a ploy by legislators to keep their minds off “bloody Kansas” for a few hours and swap bad scatological jokes.

Guano broker and his annoyed family.

Under the provisions of the Guano Act, Klinkle acquired all mineral rights on Poco Cabesa in exchange for four pigs, a two year old copy of “Leslie’s Illustrated,” and a boat-ride off their malodorous home for the olfactory-challenged clan-in-residence. (Naturally, this had no impact upon the independent kingdom of Medillo Grande, which had no guano deposits.) Then Hyman brought in his fertilizer managers who, upon seeing their new home, were none too happy with this assignment. But they got over this first impression when they saw all that prime guano. The same could not always be said about their families.

Sandoval James Ortiz in 1882, just before his big guano strike in the area now known as “Sandoval’s Blight.”

To mine guano you need guano miners. Hyman advertised for them far and wide. It was not long before the guano-encrusted portions of the little island were crawling with adventurous souls from around the globe. Riches literally lay on the ground, ready for hard-working men and women with strong stomachs and no sense of smell to come along, scoop it up, and sell it to Hyman Klinkle. Overnight, Poco Cabesa experienced a guano rush that rivaled the booms of the Klondike, the Comstock, or Sutter’s Creek, only with a much stronger odor.

Otto the Lemon Boy

Success stories abounded, luring even more dreamers to the island. One thoughtful lad earned a fortune in just three months providing tubs of lemon juice for miners to bathe in before they patronized the bawdy houses and gambling halls. A New Hampshire man netted $200,000 on just one shipment of hip-waders to the island in 1882.

Industrious laundress

Some say a Malay laundress bought her own island in the Seychelles with the guano she shook out of her clients’ cuffs. Everywhere you looked, Poco Cabesa positively festered with the fruits of the free market.

Before considering the historical impact of what some have called “The Great Guano Rush,” it is necessary to consider the background of Hyman Klinkle, the Andrew Carnegie of fertilizer.

Hyman Shlomo Klinkle was born December 11, 1836, on a small farm outside Ludwigsburg in southern Germany. His father, a brewmeister and idealistic member of the short-lived Junges Deutschland reform movement, died before Hyman was born when a fire erupted in a cafe where papa was speaking against the ban on Heinrich Heine’s writings. Tragically, Papa Klinkle and eleven fellow reformers met their end at an exit blocked by beer barrels.

Heinrich Heine

Herr Heine and his companion, Meta Klosser, escaped when they broke through a front window and eluded authorities by hiding in a pickle barrel. The lengthy gestation of Hyman by the grieving widow, Mitzy Klinkle (Hyman was born twelve months after papa’s death), created such a scandal in Ludwigburg that Mama Klinkle was forced to flee this mean-spirited talk by taking her baby boy to Stuttgart.

Life in Stuttgart was apparently much more palatable for the young widow. Public records indicate that Mitzy enjoyed the attentions of painters, artists and writers who were deeply involved in various movements leading up to the failed revolutions of 1848. This, perhaps, is a clue to Hyman’s passionate dislike as an adult for anyone associated with a “creative” art.

The widow Klinkle appears to have been reasonably particular (if prolific) in her choice of male companionship. And, times being what they were, Hyman found himself welcoming a steady stream of new brothers and sisters into the fatherless family (Mitzy was apparently a “free thinker” of her time and too liberated for the tradition of marriage). When the good people of Stuttgart finally made known their disapproval of these goings-on, Mrs. Klinkle gathered her tribe and departed for America. Her late husband had relatives living in Northfield, Minnesota, just south of the booming farming and ore cities of St. Paul and Minneapolis.

Like so many other youths of that era, Hyman went to work before he was fourteen (if only to reduce the congestion around the house). But he did not go into the mines or the mills of America’s Industrial Age, as did so many of his peers. Instead, he went to work in the office of a soap factory run by his uncle, Hans Flaegel Klinkle, in South St. Paul. Where other destitute little boys and girls learned all about coal dust and cotton fiber diseases of the lung, Hyman learned about numbers and ledgers and profit margins and the business of running a business.

Like so many other youths of that era, Hyman went to work before he was fourteen (if only to reduce the congestion around the house). But he did not go into the mines or the mills of America’s Industrial Age, as did so many of his peers. Instead, he went to work in the office of a soap factory run by his uncle, Hans Flaegel Klinkle, in South St. Paul. Where other destitute little boys and girls learned all about coal dust and cotton fiber diseases of the lung, Hyman learned about numbers and ledgers and profit margins and the business of running a business.

As he grew older, he was given more responsibilities and more pay and, according to family letters in the University of Rochester’s Klinkle Collection, made his Uncle Klinkle extremely proud. Without Hyman’s continuing financial help, Mitzy Klinkle’s clan would have foundered in the seas of penury and shame. Instead they enjoyed the benefits of a solid middle-class existence.

Unfortunately, Mitzy Klinkle met an untimely end in 1859, while traveling to Venice courtesy of Hyman’s generosity. Her ship was attacked by Corsican pirates led by a distant relative of Napoleon Bonaparte who robbed everyone onboard and killed those with German accents. The family’s grief was great, but the Klinkle clan could at least take comfort and satisfaction in Hyman’s ascent in the world of business and the knowledge that, with or without garrulous Mitzy, someone was looking out for them.

Hyman (top left) “sitting in” with the Army of the Potomac’s quartermasters’ jug band.

By this time, Hyman was a general manager for a DuPont chemical plant located in Chicago and spending most of his time on the road in search of natural resources. When the U.S. Civil War broke out in 1861, he was exempted from service due to his being the sole means of support for his many siblings. Seeing where the money would be made in this conflict, Hyman had himself assigned to the company’s munitions works and was soon selling ammunition to both the Union and Confederate forces. Commissions were good and Hyman invested wisely, going short on minstrel shows and sorghum and long on the nitrogen-rich guano needed for munitions manufacturing.

Fertilizer blenders on factory floor in St. Paul, Minnesota, circa 1879

By war’s end, the ambitious young Klinkle had saved enough to buy a majority interest in a Minnesota-based company named Twin Cities Dung & Dirt and became its president and managing partner. The predecessor of the Klinkle Fertilizer and Feed company was thus born.

The modern fertilizer industry as we know it today had its start around 1842, when Sir John Bennett Lawes introduced superphosphates to the world. The seemingly miraculous crop returns gained from using superphosphate-based fertilizer created a meteoric, worldwide demand for the product. This industry had long attracted Hyman, who was familiar with Plains farmers’ complaints about thinning soil and crop yields.

Mrs. Hyman Engels Klinkle, Summer 1902

After his purchase of Twin Cities Dung & Dirt, he set out to learn everything he could about fertilizer. That meant several trips to the famous Rothamsted Experimental Agriculture Station in Hertfordshire, England. It was also around this time that he married Gathelea Mary Engels of Duluth and built her a home in West St. Paul (there were no children).

Success in fertilizers meant a life on the road and at sea for Hyman Klinkle. But it was not a lonely life, for, on his scouting expeditions, he was accompanied by his wife and any of his siblings who he could confuse into thinking that he was taking them on a vacation. A frustrated missionary, his wife Gathelea insisted on seeking converts wherever their ship came ashore, which caused some embarrassment in ports like New Orleans, Key West, and Havana.

Hyman’s youngest brother, Hiram, remained in Minnesota and managed the Klinkle Mercantile Bank & Commercial Trust for the family. Ironically, Hiram was killed during the James Gangs’ great Northfield Raid of 1876, when he was struck by a stray shot while taking a bath. He had just moved back to Northfield from St. Paul because, as he wrote his brother only weeks before his tragic death, the Twin Cities were getting too dangerous.

Guano-ore freighters at Puddman’s Pier, 1892

As you might expect, the great guano find on Poco Cabesa made Hyman a legend during the Gilded Age. And, being a classic Gilded Age “robber baron,” Hyman gave little thought to the booming island’s quickly developing caste-like social order, its corrupt, company-town politics, or the well-being of the guano miners he affectionately called “my little stinkers.” All Hyman was interested in was good guano.

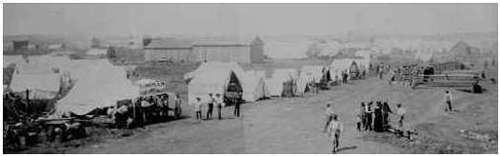

Klinkleburg during the early days of the guano rush.

Changing room at “Barking Betty’s”

Like so many of his contemporaries, Hyman attributed his miners’ lifestyles to their natural lot in life. But, privately, he suffered deep pangs of conscience when his contractors 2 joyfully handed over their company scrip (at a steep discount) to horizontal comfort parlors like the “Twisted Limb” and “Barking Betty’s,” or whiled away their scarce free hours with games of chance, cheap rum, and women with bad teeth and crude tattoos.

Another wheelbarrow of “guano gold.”

His detractors said that only Hyman’s fear of his devout Methodist-Lutheran wife kept him from taking an active ownership position in these lucrative if somewhat risque market niches. Others stated that the constant anxiety over this missed business opportunity exacerbated Hyman’s predisposition to flatulence and led to his premature demise on a St. Paul streetcar in 1881. Debates such as these, however, are a subject for those interested in opinions, not history, and your humble scholar remains concerned only with facts.

Notwithstanding his pained disinterest in his workers, Hyman (according to his letters home to his wife and siblings) eventually began to worry about what would happen to Poco Cabesa (and Klinkleburg) after the guano mines petered out. Despite the boomtown’s rowdy ways, Hyman saw his namesake tent and two-by-four metropolis as his legacy (when fertilizer is your vocation, even the faintest glimmer of a legacy shines bright indeed — especially when you are the kind of fellow who keels over on a streetcar because you are too tightfisted to hire a carriage).

Guano Exchange, circa 1891

Determined to do right by his little island, starting in 1893 Hyman deducted a small percentage from every guano receipt (charged to the miner, not the Klinkle Fertilizer & Feed Co.) and deposited it in the “Poco Cabesa Limited Trust,” which was administered by his youngest brother, Horace, at the newly formed Klinkle Bank & Commercial Exchange in Bloomington, Minnesota.

Early guano hauler.

Klinkle Fertilizer & Feed did not have employees. All miners and guano-gatherers were independent contractors who brought their guano-ore to central collection areas. They were paid by the pound and also by the quality of the guano. Since he owned the entire island (except for Medillo Grande) and all means of transportation (land and sea), it was Hyman Klinkle who set the price of guano.

Ligg Isleichen, Vienna, 1879

The terms of the Trust stated that it was to be tapped only when the island’s guano gauge ultimately reached “E.” One of Klinkle’s early biographers, Margaret Celeste Dorsett, theorized in her landmark work, “Guano Man,” that he intended the Poco Cabesa Limited Trust and Klinkleburg to be models of paternalistic authoritarian capitalism, a concept promoted by the 19th century Austrian political theorist and Theosophist, Ligg Isleichen. Other historians and biographers, however, insist that Hyman was simply sending business his little brother Hiram’s way. Whatever the reason, day by day, year by year, the legendary Limited Trust grew in proportion to the shrinking layers of guano upon which it fed.

Idled guano workers.

As Hyman had feared, even guano doesn’t last forever, especially when uncontrolled mining activities frighten the migrating masses of avian sojourners away from their traditional stop. After the last guano-freighter weighed anchor in 1899, there was not much to do on Poco Cabesa and almost everybody left (Haiti, Galveston and southeastern Florida were popular destinations).

Heading for Haiti.

However, a dedicated slice of the upper-crust and a modest crowd of those laborers who had nowhere else to go stood fast. These sturdy few, these hearty souls who proudly called themselves Klinkleburgers, remained to await an accounting of the Trust.

Trusting in prayer.

Unfortunately, to the despair of Poco Cabesans then and now, when all was said and done, the flow of funds from the Trust to the descendants of the island’s plucky pioneers resembled a ripple of subsistence as opposed to a tsunami of riches. Not enough to invest and grow. Just enough to scratch out a meager existence, keep half a dozen saloons in business, and permit the occasional coup. Or, as one disgruntled resident called it, “Just gettin’ by money.”

Klinkle House (before its demolition by irate citizens)

An emergency motion was made in the island’s Parliament to change the name of Klinkleburg to “Suckerville.” After a heated debate lasting almost an hour, it failed passage by one vote. Then everyone got drunk and went out and tore down Hyman’s now empty mansion on Gull Hill.

Hyman’s mathematical formula for population control.

The Trust was not merely parsimonious. It also had significant strings attached. To prevent writers and artists — whom, as we know, Hyman thought useless, frivolous, and depraved loafers and free-thinkers — from descending upon his tiny isle and squandering his benefaction, he established a complicated “eligible resident” restriction based on a mathematical formula having, as one factor, the number of females on Noah’s Ark. This formula was soon forgotten because higher math exceeded the mental abilities of most residents and Hiram’s wife apparently used the notepaper on which it was written for a grocery list.

“Hopeless” Hollinsworth and unidentified man during ill-fated guano panning scheme, 1904.

Faced with meager resources and very few reasons for anyone to want to visit Poco Cabesa, let lone live there, the residents of Klinkleburg saw the writing on the wall and wisely held in check their physical yearnings to avoid producing descendants who would dilute the monthly Trust pay-out. Since newcomers were ineligible for the dole and there was nothing else to attract them, this effectively ended emigration to the island and strong class divisions soon developed.

The ensuing tensions kept the non-elite residents well-mannered but extremely paranoid due to their leaders’ frequent mood swings.

The Klinkleburg Constabulary Corps, circa 1902

Angry, armed with big sticks, and determined to maintain order.

If Poco Cabesa had had anything to offer besides guano (and it didn’t even have that anymore) it might have attracted the attention of a major power. Or maybe even Spain. Instead, the island lapsed into a sleepy post-industrial stupor abstemiously funded by Hyman Klinkle’s benefaction.

|

Loyalty to petrified opinions never yet broke a chain or freed a human soul.– Mr. Twain |

|

|